According to a 1986 report by the Shanghai-based literary journal Literature Press, in Guangzhou, capital of South China’s Guangdong Province, 70 percent of high school and university students had read Chiung Yao’s works.

Yang Jilan cites individual liberation and the pursuit of pure love as the cornerstones of Chiung Yao’s fiction. These strong messages resonated with millions of young Chinese in the 1980s, planting the seeds of love and personal freedom in their minds. However, this awakening was met with strong conservative resistance.

Zoey, a 52-year-old senior editor at a Beijing-based magazine, shared an unforgettable incident from her teenage years. In 1985, when she was in middle school, one of her classmates – a top student – was caught reading Chiung Yao’s novel in class.

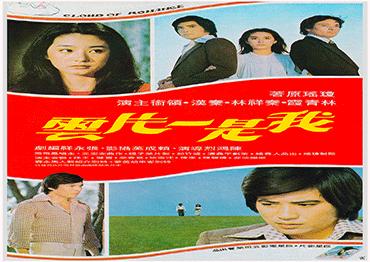

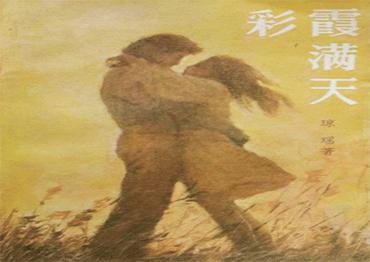

The book, Love Under a Rosy Sky (1979), tells a bittersweet story about a young couple devoted to each other since they were young teens. They endure repeated breakups and reconciliations, driven by familial and societal pressures. The novel’s cover featured the couple embracing passionately.

“Soon the whole class and the students’ families knew about it. When I went home, my grandmother sternly asked me if I had read any books like that. She didn’t know what the book was about, but the cover was enough to offend her,” Zoey said.

“In the eyes of adults back then, reading such books as a teenager was indecent, even shameful. The funny thing is, just a few years later, around 1989, my grandmother became obsessed with Many Enchanting Nights, a TV adaptation of Chiung Yao’s work that even includes a storyline about premarital pregnancy,” she added.

“Chiung Yao’s novels are page-turners, beautifully written with lyrical language and rich allusions to classical Chinese poetry. Her engaging plots, full of twists and turns, were incredibly alluring to young girls experiencing their first awakening of love,” Zoey said.

In the mid-1990s, the Chinese mainland witnessed a second wave of Chiung Yao mania. This time, it was fueled by cinematic and television adaptations rather than her novels. Millennials in China grew up with these adaptations as a formative part of their pop culture experiences.

In 1998, the period drama My Fair Princess, adapted from Chiung Yao’s novel of the same name, was a hit across China and Asia. Set during the reign of Qing Dynasty Emperor Qianlong, who ruled from 1735 to 1796, the series follows a street-smart orphan who, after befriending the emperor’s illegitimate daughter, inadvertently becomes a princess.

The story, all about love among family members and young couples from completely different social backgrounds, deeply touched the heart of the audience. The first season, aired on Beijing Television, achieved an average audience rating of 47 percent, peaking at 62.8 percent. The second season, broadcast in 1999, boasted an average rating of 54 percent, with its highest reaching 65.95 percent.

Wang Ya, a math teacher from Changsha in Central China’s Hunan Province, was born in 1990. Like most millennials, she never read Chiung’s novels but grew up watching the adapted TV series.

“My whole family loved the first season of My Fair Princess. We were so excited for the second season. I vividly remember the night it premiered. I was 9 years old, and my family had just finished a wonderful dinner at a grill house. Around 7:30 pm, we all rushed home – along with other diners – because the show was starting at 8 pm. Watching My Fair Princess together was one of the happiest moments of my childhood,” Wang said.

In addition to My Fair Princess, Wang was impressed by Romance in the Rain, a 2001 period drama adapted from Chiung Yao’s 1964 novel Fire and Rain. Set in 1930s Shanghai, the story centers on a strong-willed nightclub singer and the estranged daughter of a retired general with nine wives. Seeking revenge on the family that abandoned her and her mother, she eventually discovers the meaning of love and forgiveness through her relationship with a mild-mannered reporter.

“I loved the sentimental and nostalgic atmosphere of the show. It was beautifully shot with stunning period sets, costumes and music. The songs were melodious and poetic. Although the main characters are ‘hopeless romantics’ by today’s standards, I think it’s still a great show. Even now, when I hear the theme songs, I’m instantly transported back to the turn of the millennium, a time when people still believed in love,” Wang said.

Old Version

Old Version