little over a thousand years ago in January 1024, China’s Northern Song Dynasty (960-1279) issued a paper note, called “the official jiaozi” in the southwestern city of Yizhou, now known as Chengdu, capital city of Sichuan Province. The note is recognized as the world’s first official paper money.

Metals, mainly gold and silver, were widely used as currency back then. Copper coins had been used for millennia in ancient China as common currency for daily trade, going back more than 2,000 years. The value of metal money was backed by the metal itself, but the value of paper money we spend today is backed by the creditworthiness of the issuing government. Without these monetary guarantees, it is worth less than the paper used to make it.

Paper money resulted from the demands of an active market. Why was it created more than a thousand years ago in a place far from the center of the dynasty, which had its capital in Central China’s present-day Kaifeng, Henan Province? And why were jiaozi and other similar paper notes abandoned 600 years later?

Yi Gang, president of the China Society of Finance and Banking and former governor of the People’s Bank of China, the central bank, writes in an article in the Journal of Financial Research in October 2023 that the success and failure of the jiaozi provides important lessons on monetary policies and measures to maintain a stable currency.

Speaking to China News Service (CNS), Professor Liu Fangjian of the Southwestern University of Finance and Economics in Chengdu and jiaozi researcher Luo Tianyun, who co-authored the book Millennium Jiaozi and Chinese Currency and Finance published in 2024, the 1,000th anniversary of the official jiaozi, shared their insights on the jiaozi’s creation and its role in history.

CNS: How did the jiaozi note come about? When was it first issued?

Luo Tianyun: During the Northern Song Dynasty, Sichuan had a well-developed commodity economy [based on its prosperous tea business]. But Sichuan mainly used iron coins, not the copper coins which were in wide circulation in other parts of the dynasty. This localized money circulation, coupled with the limited money supply, as well as the lower portability of iron coins which were much heavier than copper, threatened to inhibit Sichuan’s economy, making it necessary to improve both credit and monetary instruments. So, one after another, a large number of new paper-based credit instruments were issued, such as official permits for private tea and the salt business [which could be traded on the market] and the jiaozi.

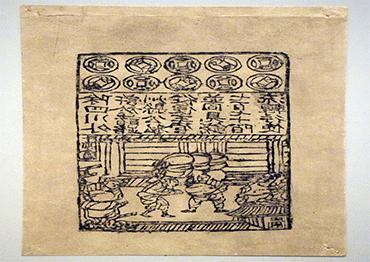

The jiaozi evolved from “private jiaozi” to an “official jiaozi.” Inspired by the Tang Dynasty’s (618-907) feiqian (“flying cash”) in its early years, the Song imperial court set up financial offices in several regions that enabled merchants to conveniently make cross-regional purchases and money transfers. Merchants coming to Sichuan to buy goods needed to convert the money they brought with them into iron coins at the offices first, then they had to deposit the iron coins into financial stores [known as jiaozi shops that could issue and print notes] that had good credit standing and allowed withdrawal services at any time. These stores handed merchants bills of exchange on a paper note [made from mulberry bark], stamped with their seals based on the amount of iron coins they had received.

As these bills facilitated commodity trading and addressed the inconvenience of carrying around heavy iron coins, they became gradually accepted by the public. During this period, stores issued their own jiaozi, which had no standardized form or fixed denomination printed on it. Rather, the denomination was handwritten on the top of the note. Later, since a single money shop was not creditworthy enough, 16 shops combined to make a joint guarantee: if one was unable to provide a withdrawal, the others would have to share the responsibility. This is the earliest “private jiaozi.”

On January 12, 1024, the Northern Song imperial court approved the Yizhou Paper Notes Office, and on April 1, it issued the first official jiaozi, backed by the local government. This meant that the currency was included in the imperial system, and had the same legal status as metal currencies like gold, silver, copper and iron. Therefore, considering the significance in the system of institutionalized currency issuance, January 12, 1024 is considered the date of birth of the world’s first paper currency.

CNS: Why did the jiaozi start in Chengdu?

Liu Fangjian: Sichuan had the conditions for paper money to emerge at that time. These included a prosperous local economy, second only to Yangzhou in today’s Zhejiang Province. It had booming brocade and papermaking industries, an advanced woodblock printing industry, and doing business on credit was widely accepted. Added to the inconvenience of iron coins, it set the conditions for developing a paper currency.

In terms of local credit conditions, Professor He Ping of the Renmin University of China’s School of Finance has said that although the jiaozi was born at a time of particular pressure due to use of heavy iron coins in Sichuan, we can attribute the creation of the private jiaozi to the trust mechanism developed among local tea merchants. The renowned Song Dynasty polymath Su Zhe (1039-1112), during his tenure as an official advisor to the emperor, noted that the jiaozi was adopted in the area and used to facilitate large tea transactions. This suggests that in the Northern Song’s Sichuan area, the jiaozi was mainly used for large transactions among tea merchants. In addition, as Sichuan is surrounded by mountains, business activities were conducted within this relatively enclosed region. In this scope of specific geographic boundaries, it is easy to do business based on trust within a certain group, and those who default would be discovered immediately. It is the trust network among tea merchants that underpinned the issuance and circulation of the jiaozi.

So, whether it was the Eastern Han Dynasty [25-220] warlord Gongsun Shu minting iron coins during his control of Sichuan, or the Northern Song Dynasty’s issuance of the jiaozi in Chengdu, the geographical advantages of the Sichuan region and the industriousness of its people contributed to its socio-economic prosperity and robust currency demand, in an era dominated by traditional agriculture. With its lesser political importance due to its remoteness from the center of imperial power, the region’s relative geographic isolation became a test bed to experiment with new forms of currency, and offered an impetus and an environment for the creation of a new one.

In addition, Sichuan had been, since the Tang Dynasty, the most developed area for papermaking. During the Song Dynasty, Sichuan’s papermaking technology saw further development, and you started to see paper made from tree bark [as opposed to bamboo]. Notably, paper was made from the inner flesh of mulberry bark, white in color and resilient in texture, and it was improved through pulping and calendaring (compressing), making it suitable for printing and circulating as paper money.

CNS: How should we place the jiaozi’s role in the origin and evolution of Chinese currency?

LF: Throughout China’s history of currency development, gold and silver, due to their scarcity and relatively high value, were appropriate for trading precious luxury goods, while copper coins of lower value were more suitable for small retail transactions to buy grain, cloth and silk, as well as other daily necessities. During the Agrarian Era [10,000 BCE-1840 CE), luxury goods made up a far lower share than daily necessities in the social circulation of commodities, so copper coins played a far more important role than precious metals such as gold and silver.

Pre-Tang China, with the Yellow River basin as its hinterland, conducted overland silk trade characterized by bartering. In the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279), when the economy shifted southeast toward the Yangtze River Basin, maritime trade began to boom. China exported raw silk, tea, cotton cloth, porcelain, lacquer and ironware in return for a large amount of silver, contributing to the precious metal’s relatively significant increase in both quantity and scope compared with the Tang Dynasty. Although copper coins still retained their function as the value standard through the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, silver was widely circulated in the domestic market.

But after the Song Dynasty, paper money failed to develop for three reasons. At that time, Sichuan’s well-developed commodity economy was still a local phenomenon, not national. Then, there was no official system to stabilize the jiaozi’s value. Finally, the “official jiaozi” was issued for both economic and fiscal purposes. Economically, it was driven by the demand for currency in the circulation of commodities. But the government also issued the money to cover financial deficits, causing severe inflation and collapse of the paper money.

However, there is no doubt that issuing the jiaozi was epochal. It freed the exchange economy from all the restraints of commodities that had been used as currencies since ancient times, such as grain, cloth and silk, as well as copper and iron. It ushered in an era of flat money underwritten by credit, instead of by commodities or metals as the medium of exchange, thus alleviating the shortage in monetary supply that had imposed constraints on exchanges. It also promoted social interactions, as well as more specialized and socialized divisions of labor.

CNS: From the perspective of monetary history, how important is the jiaozi as the world’s first paper money?

LF: The creation of the jiaozi marked the first use of paper money in human history. In ancient Asia, the village community served as a self-sufficient economic and social unit in Egypt, Persia, Babylon and so on. In the West during the Ancient Greek and Roman era, it was the slave estate, and during the Middle Ages, it was the feudal castle that served as self-sufficient units. It was not until the mercantilist era [16th to 18th centuries] that the West started to engage in external trade with nation states as trading partners with relatively large trading volumes. That is how the West embarked on the path of currency development that evolved from precious metals, through gold and silver coins, to paper money.

In China, from the Shang and Zhou dynasties to the pre-Qin Dynasty era [from the 17th-3rd century BCE], trade was mostly conducted among tribes or feudal lords, with large transaction volumes, mostly settled by gold and silver money. After that, family-based smallholders became the main economic entities of society. Transactions between those households mostly involved exchanges of needed products, which were sporadic and smaller in scale, thus precious metals of gold and silver were not used as mediums of exchange. As a result, currencies transformed to initially using seashells as money, then copper and iron coins, and finally paper money.

Despite their different development paths, the East and the West both adopted flat currency represented by paper money, suggesting that this is an inevitable development that fits the trajectories of currency development in human history.

Old Version

Old Version