According to Huang Shisong, director of the Aging Industry Research Center at Beijing’s Renmin University of China, several factors are causing the increased demand for senior-friendly accommodation in big cities.

“You have seniors who want to live with their children who already moved to those cities, while the early wave of [rural-urban] migrants are getting old too. Baby boomers from the 1960s are reaching retirement age. Plus many seniors don’t want to live with their kids or already live alone, and there are also families where everyone is aging, so there’s really no surprise that rental demand from seniors far outstrips the supply of suitable properties,” he told NewsChina.

Chen Min’s mother is one of the seniors who moved to the big city to be close to her family. When her father passed away in Baoding, Hebei Province, Chen, 36, invited her mother to come to Beijing. But her two-bedroom apartment, already accommodating Chen, her husband and two children, proved too small for ffve people. Chen’s husband was forced to sleep on the couch.

Chen decided to rent an apartment for her mother, but after she picked out five potential places advertised on a leading rental platform, the agent claimed they were all already rented.

She found another agent, who told her that all landlords he knows refuse to rent to tenants over 60 or 65, no matter who was paying. “If you pay three times the security deposit, some homeowners might be willing to talk with you,” Chen said the agent told her.

Over the next three days, Chen was refused by five agents and 18 property owners due to her mother’s age. One agent told her his platform will automatically flag customers over 65 as “high risk” and would rarely recommend properties to them.

Chen tried to contact landlords directly. In March, she viewed an older apartment where the landlord seemed amenable, until she said her mother is in good health except for high blood pressure. The owner swiftly changed his attitude, telling Chen he had to reconsider.

Later, the landlord asked Chen to prepay half a year’s rent and sign a disclaimer, but she refused, considering it age discrimination. Finally, after three months of searching, she found an apartment through a colleague.

NewsChina, pretending to be a tenant, contacted several leading property agents, including Lianjia, Anjuke and Wo Ai Wo Jia (I Love My Home), and asked about age discrimination. All denied it, claiming they neither define seniors as high risk nor have age discrimination clauses written into rental contracts.

Interviewees working in the rental sector said that age discrimination is often implicit. “It’s fine for seniors to view a property for rent, but it would be better if younger people actually come to sign the contract [on their behalf,]” He Xun, an agent who works with Anjuke, told NewsChina. “In many cases, we have to hide the fact that seniors are living in their property, otherwise few owners will rent apartments to them,” He said.

“Many owners would rather rent an apartment to a family with a pregnant woman, a baby or a pet than to a senior,” he said, “and if they find a senior living in their place, they’d rather pay double the penalty for breach of contract than continue to rent to them.”

Some landlords directly ask an elderly tenant to move to a nursing home, according to He.

Sun Ling in Shenzhen considered moving her dad into a nursing home, but the cost was too much. In a second-tier city, a place in an ordinary nursing home costs on average 3,000-4,000 yuan (US$429-US$571) a month, and more than 5,000 yuan (US$714) for a good one. If a senior needs more care, the fees are higher.

“There are highly rated communities targeting elderly people in Shenzhen, equipped with complete facilities, but they cost over 10,000 yuan (US$1,429) each month at least. It’s beyond my monthly wage,” Sun said.

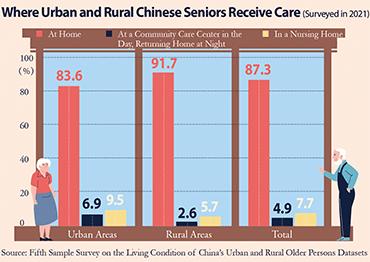

The above-mentioned 2024 survey by the China National Committee on Aging showed that only 7.7 percent of Chinese seniors live in a nursing home, and 87.3 percent still live in a home. Among seniors who would be willing to live in a nursing home, nearly 85 percent can only afford less than 3,000 yuan (US$429) a month.

“A nursing home is not the top choice because many seniors aren’t disabled and can look after themselves, and more importantly, they care about the cost. People who move to cities who want to rent a property usually have lower incomes than permanent residents,” Huang said. “Not being able to afford the cost of a nursing home is naturally a feature of the senior migrant population,” he added.

Although many local governments offer affordable apartments for rent, they are few in number and mostly target those in economic difficulties or people who are disabled or cannot care for themselves.

“The issue of seniors finding it hard to rent housing has been going on for years,” Huang said. “Lack of age-friendly apartments and landlords, and agents’ concerns about the risks, have existed for a long time. The rapidly aging society has further aggravated the supply-demand gap,” he added.

The World Health Organization describes age-friendly housing as being affordable, well-designed and safe, including features such as elevators and wide passages for wheelchairs.

Old Version

Old Version