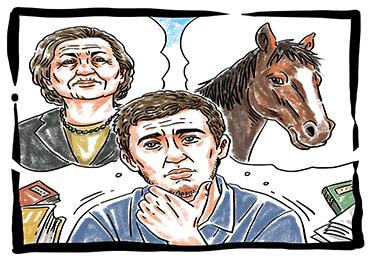

If someone had called my mother a horse before I moved to China, I would have been extremely offended. However, after a decade living here I would be inclined to forgive them, as I often make the same mistake myself. The problem is that in Mandarin Chinese the words mā (mother, 妈) and mǎ (horse,马) are distinguished only by their tones. I say only by their tones, but this is deceptive. For native Chinese speakers, the difference between tones is clear, obvious, and important. The challenge arises for most foreigners because their existing languages have rarely prepared them for the importance of subtle tonal changes. In Chinese, a tonal change can have a significant impact upon a character’s meaning, resulting in diverse words sounding almost indistinguishable to an uneducated ear. As an example, the question “is mother cursing the horse?” could be written as “mā ma mà mǎ mā?” (妈妈骂马吗?).

Thankfully, it is normally obvious from context whether someone is referring to their mother or a horse. A a result of context, foreigners who make tonal mistakes may still be understood by patient Chinese people. However, where the context of a conversation means that multiple words could seem logical or possible, words that sound very similar are trickier to tell apart. Take, for example, mǎi (买)and mài (卖). These are the Chinese words for buy and sell. Other than their tones, the words sound identical, and it is perfectly plausible in a business environment, that someone may misunderstand whether one is trying to buy or sell something. Likewise, in a social environment, perhaps one with romantic undertones, one can easily imagine an embarrassing context in which one hoped to ask (wén 问) someone something, but instead requested to kiss (wěn 吻) them. Indeed, one dreads to imagine how many meetings have been ruined by a foreigner who intended to ask a client about a sale, only to fumble their words and imply that they wanted to buy a kiss.

Although these specific challenges are related to the Chinese language, every language has subtle differences, which can baffle and confuse learners. While English is not a tonal language, small shifts in vowel pronunciation can dramatically alter the meaning of words. This is made all the more complicated by regional dialects, which are often expressed through vowel-sound adjustments. “Space ghetto” in an American accent sounds like ‘Spice Girl’ in a Scottish accent, “later” in an Australian accent sounds like ‘lighter’ in an American accent, and “fierce” in English received pronunciation sounds like “face” in many Northern Irish accents.

Unfortunately, some of the tonal differences in Chinese can be more than simply embarrassing, they can be downright offensive. For example, one must be extremely careful when talking about grass, cǎo 草 in Chinese, as a tonal variant of this word is exceedingly rude. Confusingly, a further tonal variant, cáo 曹, is a wellknown Chinese family name. Likewise, ornithologists need to be exceedingly careful when discussing the Isabelline Wheatear, a small perching bird that breeds in southern Russia and Central Asia, for while it’s Chinese name shā bī (沙鵖) is a perfectly acceptable and proper word for bird watchers and zoologists, a tonal error could see their career swiftly damaged beyond repair.

These challenges help to emphasise how important it is for foreigners to dedicate time and effort to practicing both speaking and listening in Chinese. Moreover, while the road to fluency in standard Chinese may be very long, learners should probably be grateful that they are not learning Cantonese. While standard Chinese has four tones, Cantonese has six, leading to even greater levels of confusion and complication. Thankfully, none of these words can be confused if you look at the written Chinese characters, each of which is distinct. Many Chinese people may be unaware how easily foreigners confuse many of these words, because in Chinese their difference appears self-evident. While it is understandable that foreigners struggle to learn Chinese characters, and it is perhaps forgivable that many give up trying, Chinese characters offer an invaluable insight into the language, and can help to remove uncertainties. So, before you try to ask your mother a question, and instead end up kissing a horse, consider investing a little time in learning the art of reading Chinese.

Old Version

Old Version