Nyenang Monastery, affiliated with the Kagyu School of Tibetan Buddhism, lies 60 kilometers west of downtown Lhasa. More than a religious site for monks and Buddhists, it has expanded its role by establishing an ancient classics library and an intangible cultural heritage preservation center. It collaborates with academia and universities on research related to regional history, ancient murals and the digitization of Buddhist texts. West of the monastery stands a solar power and battery storage station that generates approximately 1 million kilowatt-hours annually.

Over the past few decades, Nyenang Monastery’s tulku – Palden Pawo Tsuglag Mawei Drayang, the 11th Pawo Rinpoche – has led monks and community members in conservation efforts, such as reforestation and wildlife monitoring. These efforts have made it the region’s first zero-carbon monastery. According to Pawo Rinpoche, the storage system allows excess solar power to be saved, which powers electric vehicles for the surrounding community for free.

Pawo Rinpoche, one of the most senior figures in the Kagyu hierarchy, is a very high-ranking reincarnated tulku in Xizang. He was born in Nakchu, 300 kilometers northeast of Lhasa. In 1995, at 15 months old, he was recognized by the 17th Karmapa (Ogyen Trinley Dorje, the spiritual head of the Karma Kagyu School of Tibetan Buddhism) as the 11th Pawo Rinpoche, and thus became one of the heart sons of the Karmapa. Being a “heart son” refers to disciples who have a particularly close and profound spiritual connection with a tulku. In history, the Pawo Rinpoches have traditionally been recognized by the Karmapas, and the Pawo lineage extends to the 15th century. Successive Pawo Rinpoches have been both disciples and masters of the Karmapas.

Nyenang Valley, home to Nyenang Monastery, boasts a pristine natural environment and rich biodiversity. “Since I was young at the monastery, I would often hear that the nomads had spotted snow leopards,” Pawo Rinpoche, dressed neatly in his monk’s robe, told NewsChina at the monastery’s office in late May. “I even encountered one myself during my three years of seclusion in a mountain cave.”

In 2021, Pawo Rinpoche invited the Beijing-based community conservation NGO Shan Shui Conservation Center to conduct wildlife monitoring and research in the valley. Camera traps captured images of snow leopards and other animals. He launched the Nyenang Ecological and Cultural Conservation Center (NECCC) in 2023, hiring conservation professionals and recruiting volunteers from across China to run it.

According to NECCC staff member Liu Tao, alpine areas around the monastery are critical habitats for species like the snow leopard. In early 2023, the Xizang government approved the Nyenang Valley Natural Protection Community, a unique grassroots protected area in China. “Our protection community now covers over 50 square kilometers, with around 40 camera traps,” Liu said. “Up to now, we’ve documented seven national first-class protected animal species, including snow leopards, alpine musk deer and brown bears, 14 national second-class protected animal species and over 200 plant species. From camera trap footage, we’ve identified 13 snow leopards in total, with two adults and three cubs confirmed as permanent residents here.”

Backed by the monastery’s material and personnel support, a community-led conservation network has been established across seven nearby villages, engaging some 2,000 residents including nomads and farmers. “We’ve contracted 10 forest rangers from these seven villages to assist our center with monitoring, data collection and anti-poaching efforts,” Liu said. These are local men and women aged between 20 and 50. The center regularly invites wildlife and environmental experts to train residents, equipping them with knowledge to become eco-tourism guides in the future.

In March 2024, a nomad found an injured snow leopard with broken bones after a cliff fall, and notified monks at Nyenang Monastery. Pawo Rinpoche and other monks rushed to the scene and arranged for the leopard to be safely transported to Chushur Wildlife Rescue Center. Named Tsiring Nana, Tibetan for “benevolent goddess of auspiciousness,”the leopard received professional treatment and miraculously survived. Media coverage of the case drew nationwide attention.

A year later, as Tsiring Nana recovered, her future remained uncertain. Her right forelimb was completely shattered, so Pawo Rinpoche invited experts from other parts of China to perform surgery. Once she improved, the monastery hoped to release her back to the wild, but every conservation professional warned she would not survive. Chushur Rescue Center also proposed keeping her for breeding. “Our original goal was wildlife conservation, but this approach is emotionally hard for us Buddhists to accept,” Pawo Rinpoche said. “She is a free being, thus she shouldn’t be caged without dignity, used by humans as a breeding tool. That’s unfair and disrespectful to life.”

After negotiating with the forestry and grassland bureau, the monastery decided to try releasing her. That day, they chanted sutras to bless her. Luckily, Tsiring Nana was captured on camera traps two weeks later, healthier and stronger than before.

“This proves snow leopards and other wildlife can fend for themselves in the wild,” Pawo Rinpoche said. “It also made me realize this moment, in a way, reveals a misunderstanding many of us hold: We long for freedom, yet when faced with choosing it, we’re filled with fear. What’s more, we often imagine freedom as something external, something distant – but it’s not. Freedom is a state of the present, a choice we make in our current circumstances. More often than not, it’s a choice we can make for ourselves. Similarly, if you’re weighed down by doubts, expectations or hesitation, you can’t truly enjoy freedom. Only when you’re bold and resolute, when you dare to make your own choices, can you grasp and savor it.”

The monastery does not merely protect snow leopards. The 13 snow leopards in the valley are the Dharma Protectors that safeguard the monastery’s serenity, Pawo Rinpoche said. In 2003, a mining company wanted to operate nearby. But thanks to the snow leopards, no mining activities were permitted.

Amid societal changes, Nyenang Monastery has embraced new endeavors, from cultural preservation and education to healthcare, while prioritizing environmental protection initiatives. Above all, under Pawo Rinpoche’s guidance, the monastery has never strayed from its core tradition: authentic practice and strict self-discipline.

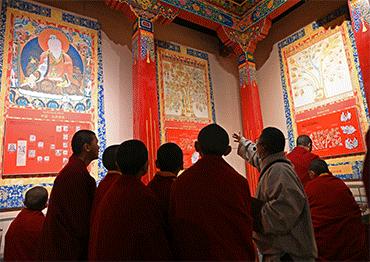

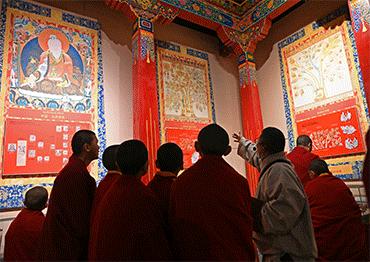

In 2016, the monastery established an ancient texts compilation group to collect Kagyu School-related ancient books and documents. By 2020, they had successfully gathered nearly 1,000 texts, Pawo Rinpoche noted. Beyond collaborating on research with academic institutions, including the Renmin University of China in Beijing, Zhejiang University and Sichuan University, the monastery has also published some of these materials, many of which had never been studied before outside the monastery.

“Overseas institutions like the University of Vienna once dominated Kagyu School research,” Pawo Rinpoche said. “But our roots are in China, so our academic research and its rightful voice should be ours. That’s why we partnered with domestic universities to launch a project called the Multi-ethnic Exchange History Based on Image Texts of the Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties. This project breaks new ground by integrating academic and monastic perspectives. Historically, academia led such work, providing frameworks and evidence. For us monks, participating in researching and exploring our history is key to building cultural identity and confidence to create mutual verification and advancement for both circles.”

For over 700 years since it was founded, Nyenang Monastery has been a hub for authentic Buddhist practice: monks uphold the Vinaya, or Buddhist monastic code, follow the Buddha’s teachings, progress through practice stages, and strive to restrain desires and subdue inner afflictions. “This tradition has weathered countless historical changes,” Pawo Rinpoche said. “To this day, our greatest pride is that it remains intact. That’s precisely why Tibetan Buddhism has not only taken root in Xizang over the past millennium, but also thrived and been passed down through generations.”

“Today, many see Tibetan Buddhism as ancient wisdom rooted in long-held traditions. Yet we often overlook a key fact: For most of history, it was more than a guardian of wisdom – it was a leader and driving force of civilization on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, and for long stretches, a pioneer in shaping its cultural landscape,” Pawo Rinpoche said.

Old Version

Old Version